I was born in May 1996, two years after Imola. I never saw Senna race live. Never woke up on a Sunday morning with that butterfly feeling in my stomach waiting for the start. My generation knows Senna through documentaries, grainy photos, and stories from those who lived it. And yet, somehow, he's my hero too.

You know when you suddenly become interested in something out of nowhere? That's what happened to me recently. Suddenly I found myself watching everything about Ayrton Senna - documentaries, old interviews, YouTube videos. Downloaded wallpapers of the red and white McLaren for my computer. And look, I was never a Formula 1 fan.

Actually, I even thought it was kind of boring as a kid. I remember being there watching Saturday morning cartoons and out of nowhere comes the qualifying broadcast. It wasn't even the race yet, just guys going around in circles to set the starting grid. I'd try to pay attention but soon got bored. Didn't understand why everyone got so worked up about tenths of a second.

I think part of my disinterest came from not having a big Brazilian name to follow in my time. There was Rubinho Barrichello, there was Felipe Massa who did pretty well at Ferrari, but it wasn't the same thing. That connection was missing, that guy who made you stop everything and watch.

`` The boy who was born for this

The more I dove into Senna's story, the clearer it became: this guy wasn't normal. Since childhood he had something different.

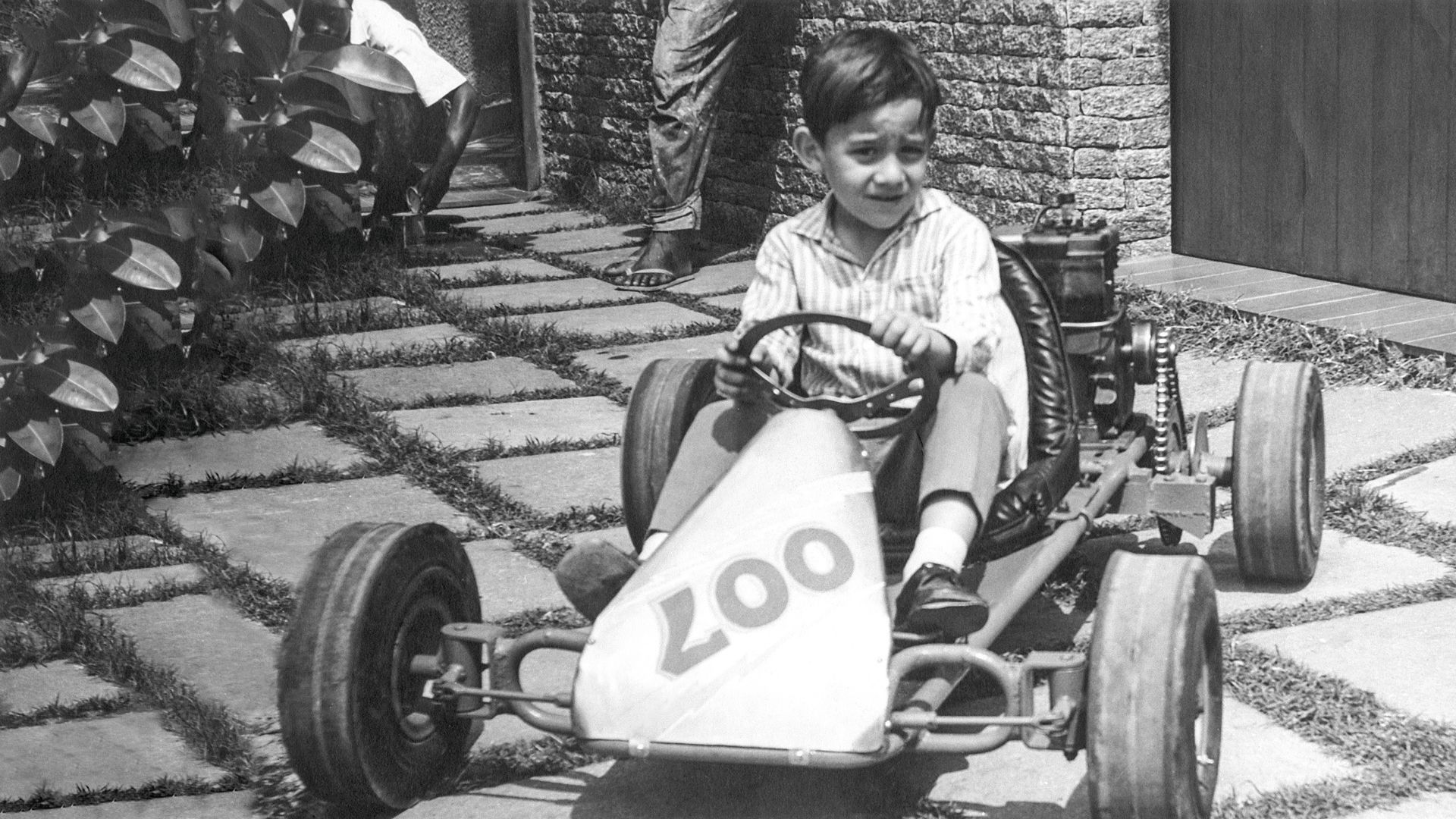

At 4 years old, he got a little kart from his dad[^1]. Most kids would just play around, take little rides. He took apart the engine to understand how it worked. While other kids his age were playing with toy cars, Senna sat in the garage surrounded by parts scattered on the floor, tightening each bolt as if it were a silent vow that one day he'd make the world spin to his rhythm.

In his teens, when he started racing karts for real, the obsession only grew. He trained on improvised tracks, trained relentlessly in the rain (just because he lost a race because of it), studied aerodynamics with books borrowed from the library, spent hours analyzing each curve, each braking point, each second he could gain. Other drivers were good. He was obsessed.

And he had a natural talent that was scary. Those perfect laps in Monaco in the rain, those impossible overtakes - it wasn't just training. It was something that came from within, an almost supernatural connection with the car and the track.

`` But Brazil had already had great drivers

And look, we had already had great drivers before him. Emerson Fittipaldi won two championships in '72 and '74. Nelson Piquet was a three-time champion - '81, '83 and '87. Twenty-three wins, twenty-four pole positions. Absurd numbers.

But none of them became the phenomenon that Senna became.

Piquet was too fast, understood mechanics better than many engineers, but had no patience with journalists. Always giving rude answers to the press, treating reporters without any respect. He was the anti-hero, and not in the cool sense of the word.

Senna was the complete opposite. Even before going to Europe, he visited the main sports newspapers in Brazil. He'd exchange cards, leave contacts, explain his plans. From there, he'd call collect after each race telling how it went - "I started second, finished first, had tire problems, the rain got in the way, etc." He delivered everything ready-made for the journalist to write the story.

This in the 80s, man. Today it seems obvious with Instagram, press relations and all. But back then? Revolutionary. He was years ahead in the communication game.

`` The Brazil that needed a hero

But there's an important detail here: none of this would have mattered if Brazil wasn't desperate for hope.

We hadn't won a World Cup since 1970. That beautiful '82 team, with Zico, Sócrates, Falcão - considered one of the best in history - got schooled by Italy and went home crying. '86 didn't work out either. Soccer, which had always been our escape valve, was going through a terrible moment.

And the country? Even worse. Rampant inflation, money that wasn't worth anything, over 20 years of military dictatorship behind us, no free elections, everything uncertain, everything difficult. National self-esteem was on the floor. We needed someone to believe in.

Then Senna came along on a Sunday morning and showed that a Brazilian could be the best in the world at something. Could go head-to-head with the rich Europeans, with the big traditional teams, and win. It wasn't just his victory. It was all our victory. It was proof that we could dream big. He made people forget, even if just for a moment, the problems of everyday life.

`` The TV that built the legend

Globo TV played a huge role in this too. Galvão Bueno, with that contagious voice, transformed laps that used to be boring into movie-worthy stories. There was a script, there was drama, there was suspense, there was good versus evil through the great rivalry with Alain Prost. It was Brazil against the world.

When Senna made mistakes - because drivers make mistakes, they're human, everyone makes mistakes - the broadcast kind of softened it. There wasn't that harsh criticism we see with other Brazilian athletes. It was as if heroes couldn't have flaws, you know? Like Superman couldn't be late to save the train from the collapsing bridge.

And it worked perfectly. Formula 1 stopped being that incomprehensible elite sport and became something of ours. People who couldn't tell a McLaren from a Williams would stop everything to watch Senna race. My mom herself, who had never watched a race in her entire life, remembers standing in front of the TV waiting for Galvão to scream "AYYYYYRTON SENNA FROM BRAZIL" and that classic Globo theme: "TAN TAN TAN DAN..." which probably just came to your memory right now.

He transformed milliseconds into national epic.

`` The tragedy that sealed the myth

And here we reach the hardest part to talk about, but perhaps the most important to understand the phenomenon: Senna's death was, in a way, necessary to build this myth.

I know it sounds cruel to say this. But it's the truth.

May 1st, 1994, seventh lap of the San Marino GP, Imola. Broadcast live to over 200 countries. An accident. Silence. That heavy silence where you feel something very serious happened. And it did. At 34 years old, at the peak of his career, Ayrton Senna died in front of all of Brazil who were still buttering their morning toast.

There's a line from Harvey Dent in the movie The Dark Knight that explains it perfectly:

Senna died a hero.

He didn't have time to age. Didn't have time to go gray, to get a belly. Didn't have time to live through decline in the sport, to endure bad seasons with small teams. Didn't have time to get involved in scandals, to say stupid things, to make wrong decisions that would tarnish his image. Didn't have time to fall into obscurity like happens with so many athletes.

He froze in time. Eternally young, eternally at his peak, eternally a winner.

Compare with other greats. Pelé aged, said some stupid things, got involved in controversies. Maradona had drug problems. Piquet gives statements that make us not know where to hide our face. Neymar, don't even get me started. They're human, made mistakes, and that's normal - but it tarnished a bit the shine they had in the past.

Not Senna. Senna remained perfect forever in collective memory.

`` The necessary phenomenon

When he died, the mourning was collective in a way I've never seen happen again.

You know what's crazy? A lot of people stopped watching Formula 1 after '94. I know several people like this. You probably do too. The person says "after Senna died, I never watched again."

This proves one thing: people didn't like Formula 1. People liked Ayrton Senna from Brazil.

He managed to transform a technical, complicated sport, full of strategy that the average Brazilian didn't understand into something exciting. Made us care about pole position, about tenths of a second, about tire strategy. Not because we understood - but because it was him there, fighting, winning.

``` Why he was necessary

I was born after. Didn't see it. But I grew up hearing the stories, saw my cousin get emotional when talking about him, or when I put on a race for us to watch. I realize there's something different there.

And the more I study, the more I understand: Brazil was so starved for hope back then that we grabbed onto that phenomenon with everything. It wasn't about understanding cars. It was about having a reason to smile.

Every race had that collective catharsis. For a few minutes on Sunday morning, the entire country forgot about inflation, forgot about problems, forgot that everything was difficult, and just rooted. When he won, we won together, when he lost, we lost together.

Ayrton Senna combined supernatural talent with obsessive dedication, genuine charisma with communication strategy, and fit like a glove at the exact moment Brazil needed a hero. The premature death sealed the myth forever.

He was more than a driver. He was the symbol that better days were possible. He was proof that Brazil could be great at something. He was necessary.

And maybe that's why, even me who was born after, who never saw a race of his live, still feel a tightness in my chest when I see that red and white McLaren.

Because some myths transcend time. And Senna, definitely, is one of them.

``` References

[^1]: Wikipedia: Ayrton Senna - "He was encouraged by his father, an enthusiast of automobile competitions and owner of Universal metalworking — the largest auto parts factory in São Paulo at the time, who built Senna's first kart when he was four years old"